Book Banning

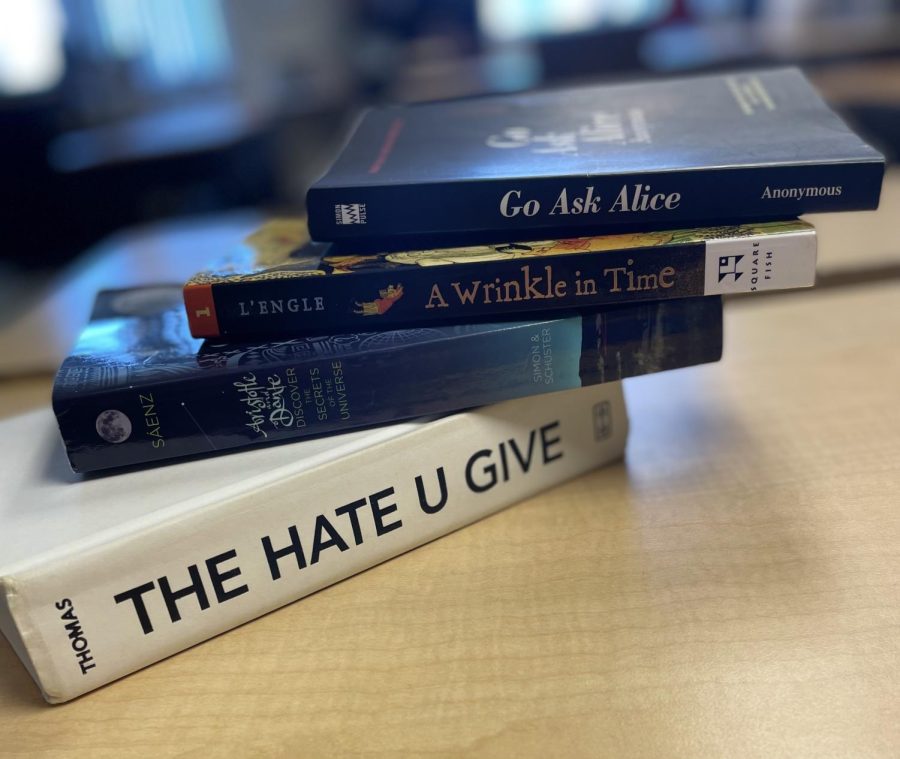

Books on topics such as race and sexuality are being banned in schools.

February 17, 2022

In the United States, book banning is the most common type of censorship, with children’s literature being the primary target.

Advocates for banning a book or a set of books fear that the contents, which they see as potentially hazardous, would sway minors. They are often concerned that these publications will convey ideas, raise questions, and elicit critical inquiry in youth that their parents, political groups, or religious organizations are not prepared to confront or find improper. Although censorship is a violation of the First Amendment right to free expression, some restrictions are legal.

“I personally think that banning books is limiting and wrong,” Sophomore Victoria Pratt said. “The whole point of books is to spread and share information that we otherwise wouldn’t have. Banning books because they don’t fit within your beliefs is controlling.”

The First Amendment safeguards students’ freedom to receive and express ideas, according to those who oppose book bans. In Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982), the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that public schools have the authority to prohibit books that are “pervasively vulgar” or inappropriate for the curriculum, but they cannot prohibit books “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” However, the Court’s decision was limited, only affecting the removal of books from school library shelves.

“The courts have told public officials at all levels that they may take community standards into account when deciding whether materials are obscene or pornographic and thus subject to censor,” According to Susan L. Webb

In recent months, books about LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Questioning/Queer, Plus) issues and race have sparked increasing conservative activity against school boards. Since they deal directly with topics of sexuality, discrimination, brutality, and narcotics, books like Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and Ellen Hopkins’ “Crank” are often challenged. No Left Turn in Education is the name of one of the challenge’s leaders. It produces book lists and recommendations to help activists in filing complaints with their local school boards. Andy Wells is the Missouri chapter’s president. He believes that works like “The Bluest Eye” are obscene and should not be taught in schools.

More books like “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Perez and “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison have been removed from Houston, Texas’s school libraries with claims of pornography, and inappropriate for certain grade levels. More parents in Texas claim the biography of Michelle Obama to promote “reverse-racism” against white people, as well as trying to ban a children’s picture book on Wilma Rudolf because it “mentions racism Rudolf faced growing up in Tennessee in the 1940’s…”

“I think books are a huge source of information, whether people use it or not, to learn different perspectives. Really, I think the only thing for me that makes a book, or any source of media, not okay for school is something that actively encourages or tells a reader to harm other people, or themselves,” Pratt said.

Tiffany D. Jackson, the author of “Monday’s Not Coming,” a 2018 novel about missing girls of color, is embroiled in a similar debate. Parents urged that Jackson’s work be prohibited for “sexual content” at a school board meeting in Loudoun County, Virginia, according to the Loudoun-Times Mirror. Jackson, who is Black, stated in an email that the novel tackles friendship, dyslexia, community, healing, and even sex, though no action is taken on it.

“Fight for Schools, a local advocacy group calling for the removal of critical race theory from school curriculums, posted on Twitter several clips of outraged parents at a school board meeting reading short passages from “Monday’s Not Coming” containing sexual situations,” Tat Bellamy-Walker from NBC News said.