The expansion of Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law to include grades K-12 leaves some students and teachers frustrated and confused by new limits on classroom discussion and curriculum.

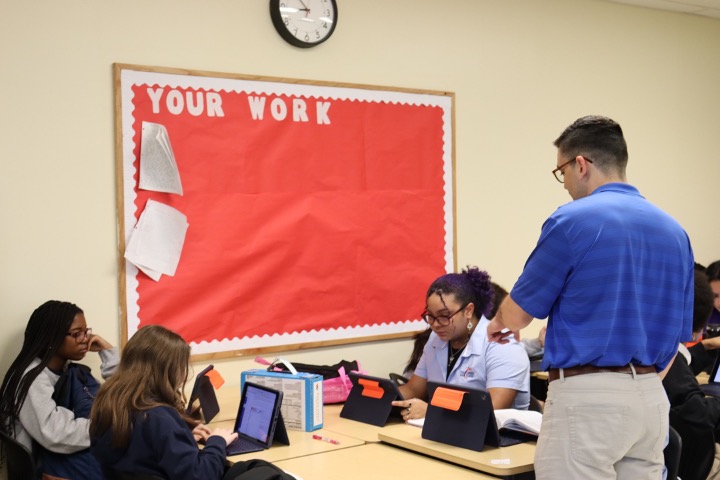

First-year English teacher Zachery Sweeney ran into one of the major side effects of this legislative change and others after being told his Cambridge English Language class is not allowed to read “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston.

“A Florida local! And one of the first African American female authors to really get famous, and she was also an anthropologist and folklorist,” Sweeney said. “So, she was a wonderful author.”

Although the “Parental Rights in Education” law itself does not ban any specific books, it does ban any lessons covering sexuality or gender identity not already in Florida standards or elective reproductive health instruction. This law and other legislation, including House Bill 1467, which requires greater curriculum transparency and strictness, mean teachers now need to select books from the Department of Education’s own pre-approved list or go through a media specialist.

However, as explained by Dean of Curriculum Krista Salazar, many schools do not have media specialists since the position requires specialty qualifications.

Sweeney and his students are not allowed to read “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by default, since Four Corners Upper School does not have a media specialist. So, there is not a specific content-based reason they cannot read it.

The inability to read this book in his English class particularly frustrated junior Caleb Miller.

“There’s a certain cheapening and desecration of the experience of these works and the knowledge and education that they can provide,” Miller said. “And it feels like students and educators are being deprived of being able to educate on the stories that they wish to, and cover topics that can be genuinely relevant and important.”

Miller feels the impact of the law on a more personal level as well. He shared that in the past he had openly discussed his own identity in academic discussions, which is no longer allowed.

“As an openly gay man, I feel there’s, again… it feels like my identity and my entire person, are being less legitimized by, you know, the state and the place in which I live. And that’s a horrible feeling. Feeling like the place in which you live doesn’t see you as someone whose identity is worth talking about,” said Miller.

The role of teachers in restricting these conversations is not entirely clear, as Salazar noted. However, she did point out that teachers are expected to redirect classroom discussions that mention topics deemed inappropriate by recent legislation.

Addressing these topics in class as the school year progresses was one concern of English teacher Marie Betts, who teaches the high school level course Great Books Honors to a class of eighth graders.

“Should they come up with a subject, you then have to think on your feet and veer off so that you’re not actually discussing that, so that one child in the class who got offended, I use that word loosely, but doesn’t run home to Ma and Pa… and say ‘This is what Mrs. Betts was talking about in class’,” said Betts.

The class, as the name suggests, comes with a heavy reading load. A reading load that has to be pulled exclusively from the DOE’s pre-approved list. Betts is pleased with the plans she and her co-teacher Julie Gardieff have for the class, but said she initially found the list did not let her explore themes and issues she wanted to.

Speaking on her experience teaching in the United States, and Florida specifically, after having moved from England, Betts stated, “I will say that it feels as though they want to control every aspect of a child’s life, instead of allowing them to be allowed to expand and appreciate other cultures, traditions, unless those cultures and traditions immediately affect America.”

Under restrictions similar to Betts, Sweeney is planning to replace “Their Eyes Were Watching God” with “Beowulf”. He still hopes to take his class to visit Zora Neale Hurston’s hometown in Eatonville though, since some shorter pieces of her writing are approved.

Even though he is looking forward to covering new novels with his students, he knows the impact of the legislation will affect more than just students’ ability to learn about gender identity and sexuality.

“We see [students] almost as much as their guardians or their parents… it kind of grieves me we can’t really be as safe a space as before,” Sweeney said. ”We have people trying to restrict us from talking about issues that they’re going to encounter and then after that, they have to handle their everyday life.”